Detained, bombed and restricted – but Joyce Mabudafhasi remains as firm as always

As the doors of South Africa’s prisons open to release the detainees, other doors bang shut. Most detainees — and many others who are fighting for peace and justice in the land — are slapped with restriction orders that make them prisoners in their own homes. The restricted people are not allowed out of their front doors from sunset until sunrise. Some have to stay indoors for even longer— in some cases, up to 20 hours out of every 24.

Family and friends become prison guards — making sure that their loved ones go to the police station every day to report.

Those with restrictions cannot work where they choose. They cannot attend meetings or any other political gatherings. They aren’t allowed out of the “magisterial district” that they are restricted to.

Many cannot speak to the newspapers.

Almost 1000 people are restricted at this time. Joyce Mabudafhasi is one of the people who has been restricted. Her story — and the others mentioned in this article — highlights the hard- ships of people who the government has cruelly chosen to silence in this way.

AS FIRM AS ALWAYS

Joyce Mabudafhasi is no stranger to the violence of apartheid. She was detained for the first time in 1976. Since then, she has been detained time and again. She has been beaten at protest meetings and badly injured in a grenade attack on her house. But through it all, Joyce has remained firm. She is as committed to the struggle as she has always been.

The daughter of a nurse and a church minister, Joyce was born in a village called Shiluvane near Tzaneen in the Northern Transvaal in 1943. After training to become a teacher, she got married.

When the family moved to Mankweng near Pietersburg, Joyce got a job in the library of the University of the North (Turfloop). She was the first black woman to be employed at the university.

After the Northern Transvaal UDF was launched in 1985, Joyce was elected General Secretary. Joyce’s work with the UDF meant that she had to travel all over the Northern Transvaal helping to organise people in this part of the country.

At the same time, Joyce was a member of other anti-apartheid organisations. As a member of the Detainees Support Committee (DESCOM), she helped the families of detained people. With the National Education Crisis Committee (NECC), she worked to solve the problems in the schools. And as an organiser for the Federation of Transvaal Women (FEDTRAW), she fought for women’s rights.

All the while, Joyce was very active in university politics at Turfloop. Those were very busy times for Joyce but she was full of energy and committment.

Restricted activists, Devyet Monakedi and Elleck Nchabeleng, hitching the long way to report to the police station in Schoonoord

“NOT THE DYING TYPE”

Joyce’s work made her a target. In April 1985, she was detained and questioned by the police three times in one day after taking part in a picket in the conservative town of Pietersburg. The picket was to protest against PW Botha’s visit to the Zionist Christian Church (ZCC) at Boyne outside Pietersburg and to call for the release of all political prisoners.

Three months later, Joyce was at a meeting in a church when the police attacked. She was so badly injured that she had to take three months off work. Later the same year, there was a big consumer boycott in the Northern Transvaal. Joyce was accused of organising the boycott and was detained again, together with her friend, Joyce Mashamba.

After she was released, she began to get some very unwelcome visits — from the police. They came to search her house almost every week. Even the family’s Christmas gatherings were disturbed by that well-known knock on the door.

In April 1986, as the family lay sleeping, a hand grenade was thrown into Joyce’s house. Joyce was seriously injured and was rushed to hospital.

Even as she lay in a hospital bed, the police continued to visit her. But Joyce was still her old self. She told the police that she was “not the dying type” and that they did not scare her. Instead, they made her more angry and more determined to continue with her work.

The grenade attack was the start of many operations for Joyce. Doctors had to remove the shrapnel and glass from her body, and even from her eyes. This time, Joyce was off work for another six months. The day before she was going to start work again, she was detained under the emergency regulations.

ALONE IN A CELL

Joyce’s detention started with five months alone in a cell at Pietersburg police station. Then she was taken to Nylstroom Prison where she again met her old friend, Joyce Mashamba. After a year, they were both transferred to Pietersburg Prison.

At the prison, Joyce found herself in good company — her friends Joyce Mashamba, Priscilla Mokaba and Maris-Stella Mabitje, who also worked at Turfloop, were also there.

On New Year’s Eve of 1988, the women decided enough was enough — they were sick and tired of being detained without trial and of being cut off from their families and community. They decided to go on a hunger strike.

The women were taken from the prison and separated, and Joyce was sent all alone to Louis Trichardt Prison, where she continued her hunger strike. Joyce lost 10 kilograms in three weeks and her kidneys began to fail. But she refused to eat until she was finally released at the end of January — with restrictions.

When Joyce arrived home for the first time in two and a half years, she found a cold and lonely house. Joyce’s four children were staying in other parts of the country and Joyce’s restrictions did not allow her to travel to see them.

Joyce’s restrictions also prevent her from being with more than ten people at one time. She must report at the police station twice a day, once in the morning and once in the afternoon. She cannot leave her home between 6pm and 6am. She cannot leave the magisterial district of Mankweng without written permission from the Minister of Law and Order.

Joyce cannot take part in the activities of many organisations or go to any meetings. And she is not allowed to enter any educational institution — which means that she cannot go back to her job at Turfloop.

UNDER HOUSE ARREST

We wanted to ask Joyce about her life under these cruel restrictions. But we could not — Joyce is not allowed to talk to the press. So we spoke to some of her friends instead.

Maris-Stella said: “If Joyce wants to go shopping or anything else, she has to apply in writing 14 days before. It is the same thing if she has to go to Johannesburg to see her lawyers or doctors.

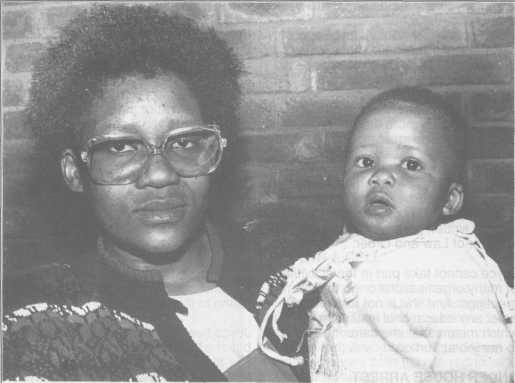

Baby Amandia with her restricted mother Lorraine Mokgosi. Amandia has never seen her father, activist Stanza Bopape, who is “missing”

“Because Joyce cannot work, she has no money. Sometimes, a friend will give her a bag of mielie-meal or another friend will give her R20. Out of this, she must try to keep the home running as well as look after her sick mother. And as a mother herself, it is painful for Joyce that she is not able to support her children.”

But perhaps the most frightening thing for Joyce is being under house arrest at night. “Joyce worries all the time that there may be another bomb attack on the house,” says Joyce’s mother, who suffered a stroke when Joyce was in detention. “And I worry that Joyce will forget to report or that she will not come back. Even if s’he goes to the shop, I think maybe they have taken her away again.”

Joyce’s mother has good reason to worry about the safety of her daughter. There have already been attacks on people under restrictions. Patrick Stali, a youth activist, was attacked in Uitenhage, but escaped alive. Others were not so lucky. Activist Chris Ntuli was murdered in Natal as he was hiking to the police station to report.

Joyce lives with this fear every day — but she knows she is not the only one. Her friends, Maris-Stella, Priscilla Mokaba and Joyce Mashamba, have also been restricted. Joyce Mashamba has been given permission to live in Johannesburg with her husband. This is the first time since 1976 that they have been able to live together.

Maris-Stella suffers from ill-health and has to get permission to go to medical specialists in Johannesburg. She received no medical care while indetention. Priscilla Mokaba has been restricted perhaps for no other reason than because she is the mother of Peter Mokaba — president of the South African Youth Congress (SAYCO).

FRIEND OR ENEMY?

Elleck Nchabeleng, the son of murdered Northern Transvaal UDF president, Peter Nchabeleng, and Joyce Mabudafhasi’s nephew, is also restricted.

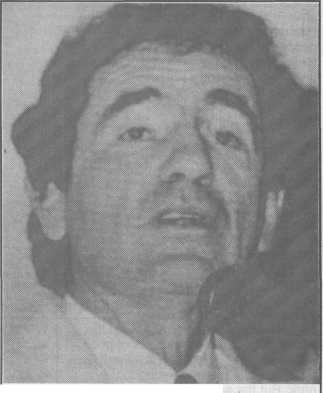

Restricted Raymond Suttner

Every day, Elleck must travel 54 km each way from his village of Apel in Sekhukhuneland to report to the nearest police station in Schoonoord. He has no transport or job, so every day he hitch-hikes. Even when he can afford a taxi, it costs R10 a day and there are very few taxis in the village. When he hitch-hikes, he has no idea whether the people who stop for him on the road will be friends or enemies. Elleck lives in fear for his life. “The idea of history repeating itself is very frightening for the whole family,” says Elleck. “My father was murdered by the Lebowa police in 1986, at the very same police station in Schoonoord where I have to go every day. In fact, this happened on the very same night that my aunt Joyce Mabudafhasi’s house was bombed.

“Even if there was employment in this rural area, I could not have a job because of the time it takes me to go to the police station every day.”

If Elleck wants to go to Pietersburg or Johannesburg to apply for a job, he must phone the police there. Often, the phones do not work in the village and he has to wait for days to get through on the telephone to ask for permission.

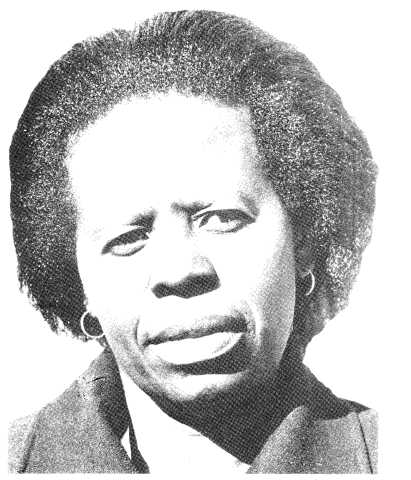

Restricted but smiling – Priscilla Mokaba

THE MANY OTHERS

Elleck Nchabeleng’s friend and comrade, Dewet Manakedi, a member of the Sekhukhuneland Youth Organisation and of DESCOM, is also restricted. Dewet has to report to the same police station as Elleck in Schoonoord, 35 kilometres from his home.

Dewet worries about being attacked by vigilantes — in 1986, vigilantes burnt his family’s home to the ground. A few months ago, his parents moved to Sebokeng in the Vaal Triangle, but because of his restriction orders, Dewet cannot live with them.

Godfrey Moleko, who lives near Potgietersrus, has to report to the nearest police station, 65 km away, twice a day. This would cost him R420 per week in taxi fare. So Godfrey has had to leave his family and move to a village closer to the police station, so that he can report on time. Rapu Molekane is a SAYCO executive member. Since his release from detention, Rapu has also been restricted. He is underhouse arrest from 2 pm until 7am the next day. During the time that he is allowed to go out, he must report to the police station.

Rapu lives in a four-roomed house with his wife and nine family members. His wife, Patience, says: “We worry about any attack that might be made on our house — like when our house was petrol bombed in 1985. Any sound like a car or a knock sends the whole family into a panic.”

Octavius Magunda is a Tembisa Youth Congress member. Octavius is only allowed out for four hours a day, between 10am and 2pm. He has to report to the police station twice during that time.

Lorraine Mokgosi, a member of the Southern Transvaal Youth Congress and women’s activist, is the fiancee of ‘missing’ activist Stanza Bopape. Lorraine has been forced to move from house to house, because some of the houses where she has been staying have been attacked by vigilantes. And now she may be charged for breaking her restrictions for taking her baby to a traditional healer without permission.

The restricted general secretary of the South African Youth Congress (SAYCO) Rapu Molekane and his wife, Patience

These are just some of the stories of just some of the restricted people. Every person who has been served with a restriction order — like Thabo Makunyane, Raymond Suttner, Cassel Mathale, Joubert Tshabalala, Louis Mnguni, Zwelakhe Sisulu, Amon Msane, Albert Tleane, Archie Gumede, Chris Ngcobo, Eric Molobi, Albertina Sisulu, Ignatius Jacobs, Donsie Khumalo, Mike Seloane, Sandy Lebese, Blessing Mphela — to name a few — have their own story of pain and hardship.

Through restrictions, the government has tried to silence these brave and committed people. Perhaps it believes that by doing this, the people’s desire for a free and democratic South Africa will go away. But history will surely prove them wrong. The people will not forget about the people under restrictions — or the ideals they are fighting for.

NEW WORDS

picket — when a group of people stand together outside a place and protest about something, or try to stop other people from doing something, it is called a picket

institution — institutions are big organisations or places, like the church, universities, schools and banks

the press — newspapers and magazines are called the press, and the journalists who write for them are called members of the press

medical specialists — doctors who are experts in one kind of medicine, for example the liver or the heart, are called medical specialists